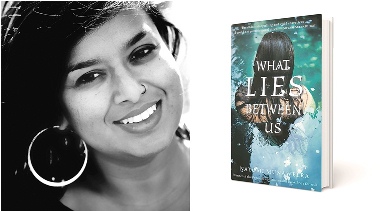

The road to publishing wasn’t the smoothest for Nayomi Munaweera, 43, but when her debut novel, Island of a Thousand Mirrors, on the Sri Lankan civil war, did get published in 2012, it met with critical acclaim. Her second novel, What Lies Between Us, treads on the fault lines of a South Asian family and maps the devastating consequences of childhood trauma with great luminosity. In this interview, Munaweera, talks about her craft, why she chose to steer clear of the Sri Lankan civil war in her new book and her bond with water. Edited excerpts:

When did the idea of What Lies Between Us come to you? How long did it take for you to finish the novel?

The first glimmer of the idea showed up in 2010. I wrote in my journal, ‘Write about a woman who…’ The deep and serious writing happened between 2012 and 2015. It took about four to five years, which is quicker than my first novel, which took nine years to write and another three to get published!

Was there anything in particular that triggered the idea of the book?

I wanted to write a novel about a character who had done something most people would find monstrous, and yet write it so intimately that people would empathise with her. My initial idea was that she was a domestic violence survivor searching for revenge, but I realised that that was too easy. I needed to up the stakes. So then, I realised what the worst crime a woman could commit was, and I made her do that.

I’m most impressed by books that make us feel for characters we would usually dismiss as inhumane. My sweet spot is when readers realise that in the right circumstances, they too might act just like my characters.

One of the things that hasn’t changed about the global discourse on parenting is the notion that “…motherhood is, if anything, the assumption of perfection.” Was it your purpose to confront that idea here?

I wanted to question our assumptions about motherhood. This book is not a defamation of maternity; rather, it’s a questioning of why we make this most important job so incredibly hard for women. I wanted to show that perfection should not be the goal. I think children just want to be loved, and so do mothers.

What Lies Between Us is about many things, but it’s far removed from the war that has defined Sri Lankan literature for the longest time. Was that a deliberate decision?

Absolutely! Island of a Thousand Mirrors is about the war that devastated Sri Lanka for 26 years. I felt I had grappled with that as much as I could. For the second book, I wanted to take on an entirely different set of questions.

For someone who has known about the strife in Sri Lanka from a distance, was it easy or difficult for you to write about it?

I think both things are true. If I had grown up in Sri Lanka, I doubt I would have written that book. First, there would be safety issues. There is the possibility that being immersed in it, I would have felt too close to write about it; lastly, the possibility of being a woman and earning my living as a writer would have been close to impossible in Sri Lanka. On the other hand, living in America and writing about a war I did not experience firsthand made me question my ability to tell the story and whether this was my story to tell.

But the book was first published in Sri Lanka and Sri Lankans have been very receptive and laudatory. Beyond that, I think the question of authenticity is not really helpful. (Vladimir) Nabokov, for example, wrote the great American novel, Lolita. He was a Russian immigrant. Sometimes, an outsider’s eye can see what the insider has forgotten to see through intimacy.

Do you think unity comes more easily to the diaspora?

Ha, of course not! The Sri Lankan civil war was funded on both sides by the diaspora. Both sides poured money into the coffers of the Tigers and the military, because they felt a nostalgia for a country that did not exist in the way they desired anymore. Poor, rural people suffered for this. I do feel that the diasporic youth are striving to get beyond the prejudices and racism of their parents.

Your childhood was spent in Sri Lanka, Nigeria and in the US; you hold a dual citizenship of Sri Lanka and the US. Which one is home?

I call both places home. They are both gorgeous places; they both have their problems. In Oakland, we face a lot of gun violence, as is the case with so much of America right now. In Sri Lanka, I have a hard time dealing with everyday sexism. So, I move between these two places and am really grateful to make a life between them.

How old were you when you left Sri Lanka? When did you move to the US?

I left Sri Lanka in 1976 with my family. I was three. We lived in various places — Lagos, Abba, Birnin Kebbi until 1984 — when there was a military coup and we had to leave Nigeria quite quickly. I learned later that we were in Nigeria because they had just finished their own civil war — Biafra — and so were recruiting South Asians to come and fill in for the generation that got massacred. In 1984, when the coup happened, we didn’t want to return to Sri Lanka because, by that time, things had gotten bad (after the deadly riots in 1983). We ended up in Los Angeles. I was 12.

Do you draw inspirations from your life to write?

Writers use memory, dream, imagination, research, eavesdropping, reading. We take all that and put it in a blender. Some writers hit chop, some hit puree. What comes out (after endless editing) is the book. So it’s impossible to tell how much is “real” or not. I do use my own life — it would be impossible not to. But, for example, I’m not a mother myself. The project of fiction is to create a world that the reader believes is true. At the end of the day, a novel is a pack of lies that tells the truth.

In both your novels, the ocean, or water, plays an important part in the narrative.

Water is the great theme that flows under the surface of many of the great novels I love. Moby Dick, for example, is a giant and gorgeous love poem to the sea. Life of Pi does the same thing. I think this is because, as a species, the ocean was our first home. We are attuned to its pull and push, the tides. Language, too, seems to follow these rhythms for me, and perhaps, more than that, my most comfortable home is in the ocean, or, at least, the warm Indian Ocean.

You also talk of racism in your novels — a polarising issue across the world. How do you see it playing out in a country that might elect Donald Trump as its president?

I think that the racists in America have found their champion and this makes them feel comfortable coming out of the woodwork. Of course, America is not the only place this is happening. I have to be hopeful and imagine that this is the last dying gasp of the outdated dinosaurs. I have great hope that the global youth are passionate about equality in race, gender, sexuality, and that they build a future that mirrors this passion.

What does writing mean to you? When did you first contemplate it as a career?

Writing means everything to me. It’s my salvation and my livelihood. I’ve always found solace in reading, and at some point, that spilled over into writing. I didn’t grow up thinking I could be a writer. That’s not a profession that most South Asian kids are told is possible. I dropped out of a PhD programme and started writing what later became my first book. I made my living by teaching. It wasn’t until I sold both books in one deal that the idea of being a writer became a reality. So, in a way, I didn’t choose writing — writing chose me.

Does the fact that you are also an artist help you in any way to visualise a novel?

I don’t really know how it works. Often, it feels like a mysterious gift that I don’t quite understand. I just plunge in and hope for the best. Sometimes, the writing is torturous, sometimes, it’s ecstatic. This seems to be a normal part of the artistic cycle and I know how to monitor it better now. I’m on my third book, and it’s true what they say: you never learn to write, you just learn to write the book you are writing.

What are you working on now?

I’m deep into the workings of a third novel. It has a very different protagonist who is thrilling to work with — he’s dangerous.

- Lanka’s post-attacks nightlife loses fizz

- On a film clip from The Godfather Part II

- Google unveils Pixel 3a, 3a XL

- Kavinda wants govt to acquire sharia university

- Federer near flawless in clay comeback

- Ignoring security warnings led to Easter Sunday attacks – Kiriella

- Blast in Lahore kills at least four, wounds 24

- Govt says cannot keep schools closed

- PM wants sophisticated technology to face global terror

- Facebook building privacy-focused social platform, says Mark Zuckerberg

Leave a comment